Understanding Anthony Davis’ Grade 2 Ankle Sprain: An Ankle Injury Primer

- Post By: Jeff Stotts

- Date:

- Category: Break Down, NBA

The 2016-17 NBA season is nearly here as team begin to trim down their rosters and ramp up workloads throughout training camp and the preseason. Unfortunately the increase in activity is accompanied by an increase in injuries as players begin to suffer an assortment of ailments. Over 75 injuries have already occurred since training camp opened league wide with multiple players expected to miss the start of the regular season. One of these injuries was recently suffered by Pelicans big man Anthony Davis during the team’s exhibition game in China. Marc J. Spears of ESPN’s The Undefeated is reporting Davis’ ankle sprain is a Grade 2 sprain.

Pelicans big man Anthony Davis expected to be out 10-15 days after suffering a Grade 2 ankle sprain in Beijing, source told @TheUndefeated. pic.twitter.com/cZ5axRRpvQ

— Marc J. Spears (@MarcJSpearsESPN) October 12, 2016

Davis’ ankle sprain isn’t the first of the season and it certainly won’t be the last. Nearly 200 ankle sprains were reported during the 2014-15 season alone, making it one of the most common injuries in the NBA. As a result, InStreetClothes.com has dusted off its ankle injury primer to help breakdown this frequently occurring ailment.

Forming the Ankle

Anatomically the ankle joint appears quite simple. It’s made up of three bones, the tibia and fibula of the lower leg and the talus of the foot. However the functional unit that is the ankle is actually comprised of three different joints.

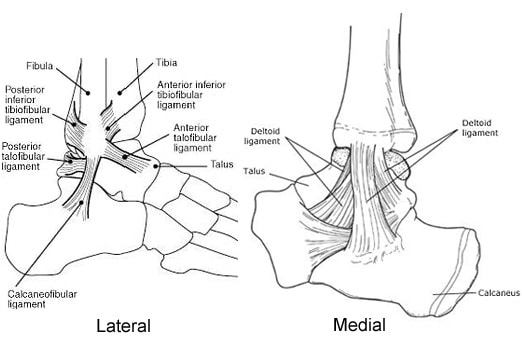

The first is the talocrural joint or the “true” ankle joint. It is formed from all three aforementioned bones and is involved with the up-and-down movement known as plantar flexion and dorsiflexion. Ligaments located on both sides of the leg and foot stabilize this area. On the inside, or medial aspect, of the ankle is the strong deltoid ligament that prevents excessive inward movement or eversion. Three additional ligaments are located on the lateral or outside of the ankle. These ligaments, the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), and the calcaneofibular ligament, (CFL) are the most vulnerable to injury and are sprained while the ankle is forced into inversion following an awkward step or when landing on the foot of another player.

The next joint involved in the ankle is the subtalar joint and is formed between the talus and the calcaneus. Here the motions of inversion and eversion are made possible. Like the talocrural joint, ligaments fortify the subtalar joint.

The final joint included in the ankle is the distal tibiofibular joint. It is located at the bottom of the leg, where the tibia and fibula join with the talus. A strong ligament known as the interosseous ligament stretches across the joint to connect the two lower leg bones while two additional ligaments, the anterior and posterior tibiofibular ligaments, assist in stabilizing the ankle mortise. Any injury that occurs to these ligaments is classified as a “high ankle” or syndesmotic sprain.

Grading Injuries

The ligaments of the body connect bone to bone. To allow for mobility and stability, ligaments have inherent viscoelastic characteristics that allow them to be both viscous and elastic. Simply put, a ligament can withstand an applied stress by rearranging its basic makeup to better provide stability. However each ligament has a very specific yield point and failure point. When the amount of stress pushes a ligament beyond its yield point, a sprain occurs. Microtrauma to the fibers that make up the ligament is considered a mild or Grade I ankle sprain. Basically the ligament has been overstretched but remains intact as a whole. Players with Grade I sprains may not even miss a game.

A Grade II sprain occurs when particular fibers of the ligament fail and is often referred to as a moderate sprain or a partial tear. Grade II sprains are generally more painful and limiting. The associated symptoms are more severe with high amounts of swelling usually occurring. As a result these injuries require intensive treatment and extended rest.

Finally a Grade III sprain is a crippling and severe injury. These injuries result in a total loss of function and stability. Grade III sprains often require a considerable amount of rest and in some rare cases surgery.

Furthermore, Grade II or III sprains are more likely to have long-term ramifications, primarily on the stability of the affected joint and the likelihood of reoccurrence. In these injuries, the ligaments have passed their yield point. Once this has occurred, its strength and integrity remains forever altered. The concept is similar to a rubber band. When a rubber band is new and fresh from the package it is stretchy yet strong. As it is used over and over again, the rubber band is slowly worn down, moving past its yield point. The once strong rubber band becomes stretched out, decreases in strength, and loses its elasticity. A sprained ligament acts in similar fashion. Once a ligament has been stressed past its yield point its physical makeup remains perpetually effected, though various treatments and rehab protocols can return the ankle close to its original state. Still once an ankle has been sprained it remains more susceptible to being aggravated and re-sprained.

Accompanying Injuries

Sprains rarely occur in an isolated manner. The violent nature of the injury often includes damage to neighboring structures. Strains to the muscles of the ankle are common with a sprain as the involved tendons are also overstretched. Injuries to bone are another regular occurrence.

Avulsion fractures frequently accompany medial ankle injuries as the deltoid ligament pulls away a small piece of bone. A bone contusion or bone bruise can occur if the stress of the incident causes damage to the outer layer of one of the involved bones. The injuries are not as severe as a fracture but require additional time to heal. The body’s recovery response treats bone bruises just like a fracture filling in the damaged area with new bony tissue.

Recovery and Rehab

The timeline of recovery widely varies based on the severity of damage, the involved tissues, and a multitude of other variables. Generally speaking the first phase of recovery involves controlling the associated symptoms like swelling and pain. An injured player may be placed on crutches or immobilized in a walking boot to minimize the amount of weight placed on and through the injured joint. A progressive rehab protocol can be initiated once the medical professional involved feels the player is ready. The preliminary focus of rehab is on regaining and retaining range of motion. The next step concentrates on strengthening the area and insuring proper muscle function. Finally the athlete will transition to basketball specific drills. Additional work on lateral movement is often necessary to assure the ligaments are capable of withstanding the applied stress.

Davis’ progression over the next few weeks will ultimately determine his availability for Opening Night. He has previously missed time in his career due to multiple ankle sprains and a stress reaction in his ankle, though each of those injuries occurred on the opposite ankle. Regardless this isn’t the start the Pelicans or Davis envisioned as they collectively look to move past the injury woes that defined last season.